Netsuke Subjects – An Introduction to Japanese Performing Arts

Annegret Bergmann

As a student I was working at an auction house specialized in Asian Art in Cologne, which provided me with the great opportunity to get close to the objects I was studying and even take them into my own hands. Here I also came across netsuke for the first time, litte art objects nowadays obsolete in Japanese daily life. Netsuke, are a carved, button-like toggle that secured the cord of a container hung from the kimono’s sash at the top of it. Over time netsuke evolved from utilitarian objects to little works of art expressing great craftmanship. When western closing was introduced to Japan during the Meiji-Period (1868-1912) a great number of netsuke migrated to the West. One of the most important collectors was the German Albert Brockhaus (1855/1921), encyclopedia publisher, who bought his first netsuke in 1887, a seated frog from Suzuki Masanao in a toyshop in Paris in 1887. Until his death his collection rose to more than 2000 pieces. In 1905 published a book containing the descriptions of around 1200 netsuke. Its second edition of 1909 containing also information on contemporary collectors and revealed the great enthisiasm on these marvellous pieces in Europe. Many of the enthusiastic first collectors had friends living in or visiting Japan which helped privide further information. Ever since netsuke are a much appreciated object of art connosseurs and collectors.

At the first International Netsuke Symposium in Japan, held at OAG Society in Toyko in October 2010, I had the opportunity to talk about netsuke sujets related to Japanese performing arts, of which some examples are represented in this article. Of couse, these examples could only provide a glimpse on Japanese performing arts and introduce a small part oft the rich theatrical world in Japan. All the netsuke example presented have been auctioned Kunsthandel Klefisch, the auction house I mentioned above.

Japanese theatre is always accompagnied by music. (No. 1: musician, w 5,7 cm) Here we see a musician playing the shamisen, an instrument imported to Japan at the end of the 16th century from the Ryūkyū kingdom, todays Okinawa. In front there is a drum, taiko in Japanese. Both instruments play a significant role in Japanese performing arts. Taiko is played in the entertainment of the gods, the kagura dances at Shintō-shrines, the dignified Nō-chanting is accompagnied by drums and a flute, and Kabuki and Bunraku theatre are nothing without its musicians and narrators, on and off-stage. But let us first take a look into the beginning of performing arts in Japan.

A little excursion into the age of the gods will lead us to this fierce looking hero, Susanoo no mikoto, a god associated with wind and rain. ‚Records of Ancient Matters’ (Kojiki) and ‚The Chronicles of Japan“, (Nihongi/Nihonshoki ) both describe the birth of entertainment in Japan. And this deity is the one who triggered it. (No. 2: Bowl ivory, disk shibuichi,∅4,2cm). In this scene we see him standing on a rock with his famous sword drawn, expecting the eight-headed dragon. The beast was about to catch a girl from an old couple, but our hero Susanoo saved her from this terrible fate by tricking the eight-headed beast with sake and finally killing it. After the battle, Susanoō found a magnificent sword endowed with supernatural powers and presented it to his sister, the sun goddess Amaterasu no ōmikami, as a gesture of atonement and respect.

Just as in human families, brother and sister frequently quarreled. To escape Susanoō’s mischief, Amaterasu hid herself in a cave in the earth, and blocked the entrance with a huge stone. So the sun would not rise and the world was cast into darkness. After all else had failed to persuade the sun goddess to come out of hiding, the gods of the universe decided that the goddess Ama no Uzume should try to get Amaterasu out of the cave. So Ame no Uzume danced on an upturned tub. As her ecstatic performance turned into a lewd and seductive striptease in front of all the other deities, they burst into laughter. This made Amaterasu so curious that she peeked out of the cave. At this point the she was pulled out and the sun rose once again. This was the first performance in Japan, with Ama-no-Uzume as the main actress and the myriads of gods as spectators. This mythical „sacred striptease” gave rise to the rite of kagura, where the priestess acts as of Ama-no-Uzume and the audience consists of temple visitors. Kagura began as sacred dances performed at the Imperial court by shrine maiden (miko), who were supposedly descendants of Ama no Uzume. Over time, however, these dances performed within the sacred and private precincts of the Imperial courts (mikagura), inspired also popular ritual dances, (satokagura), practiced in villages all around the country. (No.3: Bowl ivory, shibuichi-plate, ∅4,1cm.) In Kyōgen, the comic interludes between Nō dramas, Ama no Uzume is depicted as Okame, a woman who revels in her sensuality. Therefore her mask reflect that humorous aspect (No. 4: Okame mask, stag antler,∅4.5 cm). Okame is considered to be the goddess of mirth and is frequently seen in Japanese art. Here we see Okame as a miko, dancing with bells and gohei, strips of white paper hung from branches, in her hands.

Nō dramas evolved from the traditions of sarugaku, dengaku, and other folk agricultural rituals. Sarugaku originally included acrobatics, juggling, miming and conjuring, which were performed together with dances and rituals at shrines and temples. The dance and performance art of dengaku, associated with agricultural traditions, also merged into sarugaku. By the 11th century, comedic sketches were incorporated into the performances and eventually acrobatics were abandonned. As the art evolved, music arrangements, words and gestures began to be standardized. By the Muromachi period (1392-1568) the dramatic plays became nō plays, and the comedy plays became the comic interludes known as kyōgen. Both forms became very popular through the patronage of the Ashikaga Shōgun Yoshimitsu (1358-1408). The Patronage of nō by the ruling classes continued with the successive rulers of Japan until the end of the Meiji-period in 1868. There are about 240 plays in the current repertory of nō, and the majority of them were written by the end of the Muromachi period

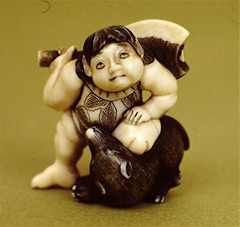

A tradition that grew out of sarugaku is the Okina dance (okinamai) and with its vigorous stamping and shaking of bells, it is a prayer for agricultural prosperity. It is still part of the nō performance repertory. Okina and Sanbasō at some point became the predominant characters in the dance okinamai. Okina and Sanbasō masks both have similar carvings and expressions. (No. 5: Sanbasō dancer, 5,7 cm high).

Sambasô is also one of the most important ceremonial dances in the Kabuki theatre. In the early days of kabuki the Sambasō used to be performed early in the morning as an opening and purifying ritual on stage. Today there are many more theatrical versions of the Sambasō dance that appeared as part of the regular program (No. 6: Sanbasō in wood, face and feet ivory, 5,8 cm high).

But still we will stay a little longer in Nō and return to the subject of masks. This is a netsuke hannya mask (No. 7: Hannya mask, 6 cm high). The hannya mask is the vengeful and jealous woman turned demon. Pointed horns, metallic eyes and teeth, and the expression all exhibit the full wrath, anger and resentment of her nature. The origins of hannya masks may have come from early snake masks, but most likely the image was taken from painted hand scrolls of stories and legends of the Muromachi period. The coloring of the face also signifies the degree of passion in the demon’s anger. The mask is worn for example by the protagonist in Nō in the play ‚Kurozuka’, about a demon who first appears in human form to trap the unwary. Like many others, this Nō play has been adopted to Kabuki, but no wooden mask is worn here – the jeoulosy and anger is expressed in the elaborate make-up kumadori.

Now let us turn to Kabuki heroes in netsuke. Sasaki Takatsuna (1160–1214) was a Japanese commander in the Genpei War, the great conflict between the Genji (Minamoto) and the Heike (Taira) clans at the end of the 12th century. The wars ended with the victory of the Genji and Minamoto no Yoritomo becoming the first shōgun. Of course numerous Kabuki plays evolve around the Genpei wars, often depicting our heroes living a secret life undercover to support their clan respectively. Their tragic and often self-sacrifying fates have fascinated the kabuki audience for centuries. Just as in this netsuke, in art Takatsuna is often shown racing his friend in arms and Minamoto retainer Kajiwara Kagesue across the River Uji atop his white horse, Ikezuki, to be the first to engage in the battle of Uji in 1184 (No 8: Takatsuna atop his horse, crossing the river Uji, ivory, H 4.3cm high, signed Kiyozumi). Takatsuna saved Yoritomo’s life at one of the battles and aided in the destruction of the Taira following the end of the war. As a result, he was rewarded with the position of governor, which he, after a couple of years, abandoned and retired as a priest to Mount Koya. The play ‚Sasaki Takatsuna, A betrayed promise’ written in 1913 by Shin-kabuki playright Okamoto Kidō evolves around the betrayed promise of Yoritomo to Takatsuna and ends with Takatsuna’s entering priesthood, just as it really happened.

But history and thus kabuki plays and netsuke sujets represent not only heros but also heroines like Tokiwa Gozen. (No. 9: Tokiwa Gozen fleeing with her three childre, ivory, 4,2cm high)

Lady Tokiwa Gozen was married to Minamoto no Yoshitomo (1123-1180), who was killed in 1180. She fled from the Taira forces with her three sons, concerned that the Taira would kill her boys. But her mother was captured and threatened with torture and execution by the their leader Taira no Kiyomori (1118-1181), if Lady Tokiwa and her children were not found. To save her mother Lady Tokiwa returned to Kyoto and surrendered to Kiyomori. By becoming his mistress, she was able to free her mother and spare the lives of her sons, one was Minamoto no Yoritomo, who would become shōgun and one Minamoto no Yoshitsune (1159-1189), who also became a famous warrior and of course hero of many Kabuki plays. But also Lady Tokiwa’s true love and loyalty is featured in a kabuki play. In ‘Ichijō Ōkura Monogatari’, ‚The Story of Lord Ichijō Ōkura’, the lord feigned madness to secretly serve the Genji cause against the then ruling Taira. Lady Tokiwa was married to him, after Kiyomori was fedup with her as his mistress, assuming that Lord Ōkura was a close alley. In the final act of the play Okura confesses that he has secretly vowed to kill Kiyomori some day and that Tokiwa too, with patience and fidelity, has been plotting the same. Although Tokiwa became his wife, she has continued to honor both her late husband and the Genji clan.

Now let us turn to another kabuki hero. We start again with a netsuke. This wonderful piece in ivory and shibuichi illustrates a famous scene in iroe takabori. We see Watanabe no Tsuna fighting the demon at the Rashōmon gate in Kyoto (No. 10: Demon fighting Watanabe no Tsuna, bowl ivory, disk shibuichi, iroe takabori, ∅5,2 cm). Watanabe no Tsuna (953-1025) was a retainer of Minamoto no Yorimitsu (944-1021) and features in many of Yorimitsu’s legendary adventures, and aids him in fighting many monsters, beasts and demons. According to legend, in late 10th century of the Heian Period of Japan, Ibaraki, a notorious demon, resided at Rashōmon Gate in Kyoto. The heroic samurai Watanabe no Tsuna defeated the cruel Ibaraki in a fierce battle and severed an arm of the demon. In pain the demon ran away leaving his severed arm with Tsuna. A few days later, an elderly woman appearing to be Tsuna’s aunt came to visit Watanabe and asked about the fight with the demon. Tsuna, suspecting nothing, even showed Ibaraki’s arm. At that moment the aunt revealed herself as being Ibaraki in disguise, grabbed the arm and escaped from Tsuna’s mansion. In Kabuki this legendary fight at the Rashōmon was performed as a dance drama in 1883 at the Shintomiza in Tokyo. The story is basically the same but has a really showy ending, just as befits Kabuki

In another tale, Tsuna accompanies his master to the hut of a man-eating hag. There they find a boy, who had been brought up among animals and endowed with superhuman strength. The boy requests that Yorimitsu allow him to become one of his retainers, and he accepts, giving the boy the name Sakata no Kintoki. This cute netsuke showing Kintoki takes us back to the early days of Kabuki, when this hero inspired one actor to invent a completely new acting style (No. 11: Kintoki fighting a bear. Ivory, stained details, signed Karaku, 4cm high). As you all know Kabuki started as a kind of all female prostitution promotion program in Kyoto. Its legendary founder, Okuni, was from the vincinity of the Izumo Shrine. As a wandering miko or shrine maiden she was collecting money for her shrine and made her living by performing sacred dances. Her performance in the dry riverbed of the Kamo River, became famous, especially because of their sultriness and sexual innuendo. The earliest performances of kabuki were dancing and singing on a Nō-stage with no significant plot. Pretty soon other women, namely prostitutes, made use of this Okuni’s popular new invention and put it on stage themselves. The shamisen was the popular instrument used in these performances. But these all-women Kabuki was forbidden in 1629. Its successor, the young boys Kabuki (wakashū kabuki) only made it into the 1650s. After 1653 all Kabuki actors had to be adult men, which was definately a blow to their main marketing strategy, their sexappeal. To cover this deficit, Kabuki theatre became more elaborate with real dramas on stage. Still today it consits of music, ka, dance bu and acting scills ki. Early kabuki plays all delt with love stories in the red light district. Kyoto kabuki stars (like Sakata Tōjūrō I and the first mega star, the female impersonator Yoshiyawa Ayame) fascinated their audience with their refined and very emotional performances. Edo, the residence of the shōgun, was a thriving city with little female inhabitants, but a lot of samurai who were obviously not so interested in refined acting as the noble audience in Kyoto. And now we are back at Kintoki, our man with superhuman power. The most popular kabuki actor of the early Edo-kabuki, Ichikawa Danjūrō I (1660-1704) invented an acting style, called aragoto that inspired the Edo audience. The expression is an abbreviation of aramushagoto ‘reckless warrior matters.’ This bombastic acting style is exagerating all the aspects of the role (acting, wig, make-up, costumes, props, dialogues) to portray valiant warriors, fierce gods or demons. The characteristic aragoto- make up, kumadori, was not introduced until 1684 or 1685. Its origin is still debated. The possible painted face of Chinese theatre is not convincing to me. I prefer the influence of Buddhist statuary. Not only Danjūrō acted in aragoto-style, also his contemporaries Nakamura Heikuro and Nakamura Denkūrō as well as his successors Danjūrō II and III perfectionated the style and the make-up. Kamakura Gongorō Kagemasa is one of the most famous aragoto-heroes of the Kabuki stage. (No. 12: Kagamibuta. Actor in Shibaraku, ivory, shibuichi, ∅4,3 cm) As stated previously, the aragoto kumadori is used for special characters, and is probably one of the most recognizable features of Kabuki. The exaggerated red lines symbolize veins popping from the face, which represents the brashness, vitality and masculine vigour of the characters. Even though they are not seen in the kagamibuta, this small peace of art represents all the power and vigor of the role.

Still today netsuke, compagnions of Edo-period daily life, give testemony of how close the people felt to performing arts. Something that might be missing today?

(注)アンネグレト・ベルクマンさん(Annegret Bergmann )は,日本演劇研究家であり、ベルリン自由大学歴史文学部講師でトリア大学第二学部(言語文学部)博士課程に在籍している。またIT企業法務研究所研究員でもある。日本で20年間暮らし日本文化を研究、現在はベルリン在住。歌舞伎、浮世絵の専門家でもある。

2010年10月22日から24日まで東京のドイツ文化会館で開催されたOAGドイツ東洋文化研究協会主催「根付シンポジウム(講演会・デモンストレーション・展示会)」に招かれてベルリンから一時帰国した。

ベルクマンさんはシンポジウムの中で、「根付から読み解く日本の伝統芸能」と題して講演をしている。

「根付シンポジウム」の開催要領では開催意図が次の通り記されている。

“根付とは、江戸時代において、印籠や巾着、煙草入れなどの提げ物を腰の帯にさげて携帯するため、紐の先に結わえて使用する滑り止めとして作られ、装飾美術品の域までに発達した細密彫刻です。根付は、明治時代以降、世界中の多くのコレクターにより収集される美術品となっています。

有名な百科事典の出版者であるアルベルト・ブロックハウスは1887年(明治20年)、パリの玩具屋で初めて、蛙型の根付を購入しました。今にも飛び跳ねそうなその蛙の彫刻は、のちに有名な根付師、正直の作であることが分かりました。その後ブロックハウスは、パリとロンドンを訪ねるたびにコレクションを増やしていき、15年の間に1000以上の根付を収集し、さらに1905年(明治38年)、根付についての本を出版しました。この本は評判となり、1909年(明治42年)、1924年(大正13年)にも重版されました。

当シンポジウムにおいて、国際的な根付の専門家が、根付の歴史と、日欧において根付を収集する意義についてご紹介します。また、ブロックハウスの功績についても紹介されます。“

なお、ベルクマンさんは2010年11月1日放送のNHK教育テレビ「視点・論点」で根付についてレクチャーを行った。

(注記:IT企業法務研究所代表研究員 棚野正士)